September 2022 was a strange time here in the UK. With the passing of Queen Elizabeth II, phrases like ‘end of an era’ and ‘long, devoted life’ were being bandied about by the press, neighbours, and on social media, but none of it really seemed to encompass the strange feeling of loss that had so suddenly settled over everything.

It was difficult to know how to feel. Is it okay to grieve for someone you never met? Is it right to grieve for something that had no direct impact on your life whatsoever? We were going about our lives without any physical interruptions, but pretending everything was normal somehow felt hollow and seemed to disregard the immense loss, physical or not, we had suddenly, collectively experienced.

Personally, I felt the loss keenly, though even now I would struggle to explain why. As an Australian, the monarchy has always held for me a kind of historical fascination. On a slightly more tangible level, The Queen was just always there, a kind old lady somewhere in the distance, a reassuring, indomitable presence. (Actually, I think Kevin Rudd summed it up pretty well when he was interviewed on the BBC, when he said ‘she was like our nanna’.) As long as she was there to tell us everything would all be alright (who could forget her moving message during the Covid pandemic?) we could be sure it would be.

So when we suddenly didn’t have her any more, what were we to do?

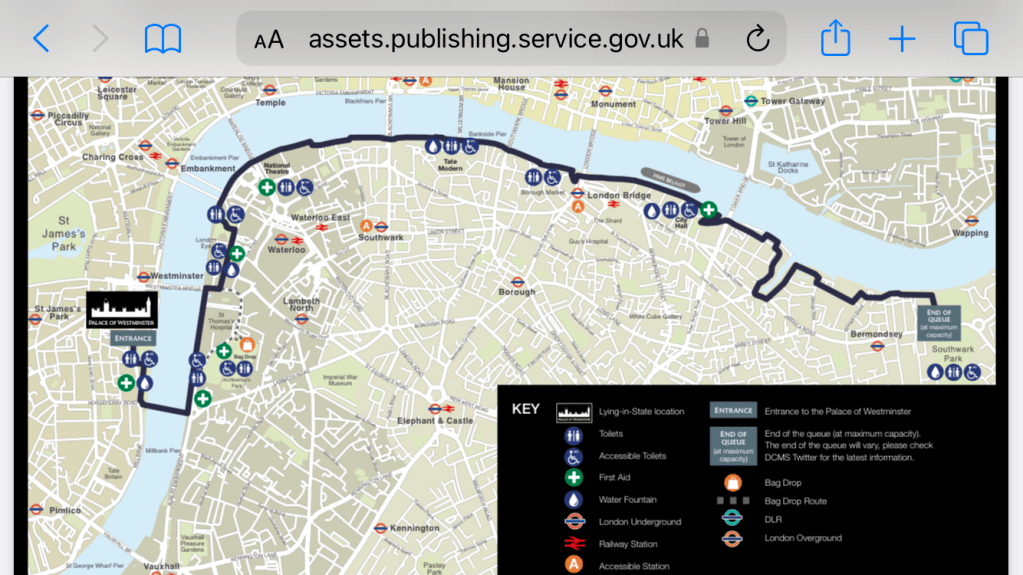

I’m not ashamed to admit that I was incredibly sad – in fact I was a little taken by surprise at how deeply I was affected. I found myself continually distracted and glued to the television. The BBC, which of course had been prepared for this eventuality for 70 years, rose to the occasion as royal commentators, former household staff members, honours recipients and anyone who had a funny story to tell were brought out of the woodwork to comment and share their experiences. My work sat on my desk, ignored, as I watched images of the queen’s coffin being driven through Scotland and as people filed past as she lay in state at Edinburgh cathedral. Then she was brought down to London, and we were informed that members of the public would be able to pay their respects at Westminster Hall. A route along the river was drawn for people to line up, portaloos were brought in, and the phenomenon of The Queue began.

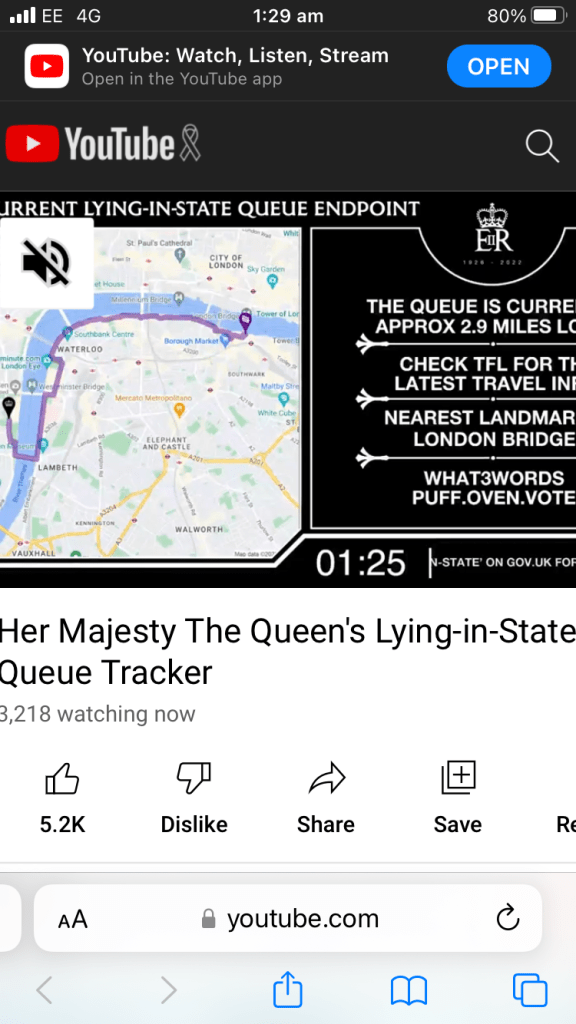

It was a simple enough concept, and not a new one, but to the surprise of many the thing developed a life of its own. People began queuing days before the Queen’s coffin even arrived, camping in the Victoria Tower Gardens, the park south of Westminster Palace. By the time the doors opened and people began filing past, it was over two miles long, starting with a zig-zagging snake through the Gardens, over Lambeth Bridge and along the South Bank almost to Tower Bridge. It even had its own website, with a live tracker informing us where the end point was and the estimated waiting time. When it got to Southwark Park, about five miles away, they closed it off, so people were forced (or perhaps it just never occurred to them not to) to queue for The Queue. ‘Only in Britain could this happen’, people said, and I’m sure it’s true! News bulletins kept us updated on its progress and reporters chatted to randomly selected people to get a sense of what it was like, and from how far away people had come to join it. Most reported steady movement and a feeling of camaraderie amongst strangers who were all there for the same noble purpose. Despite warnings of potential wait times up to 24 hours or more, people weren’t put off. They flocked in by the thousands – more than 200,000, it was estimated. People were fascinated by it. They stuck cameras in Westminster Hall, and ran a live feed to televisions across the nation. It’s a phenomenon lately called ‘slow television’ and people were utterly absorbed by it – despite the fact that nothing ever changed except the guards on duty every quarter of an hour, and the faces of people filing past, most of which were wiping their eyes as they emerged and filed past the spot where the camera was. Maybe it was a morbid fascination, but it was a fascination nonetheless, and I couldn’t take my eyes off it. I felt very far away, and the sense of needing to do something became greater and greater. In the end, I could no longer sit and watch, and it was no use trying to get on with things; I needed to be part of it, which meant I would have to go in.

I decided to go on the Wednesday evening and join The Queue overnight. It might be shorter than during the day, I reasoned, and actually that fitted better with my schedule, as I could go home and have a sleep on the Thursday. I got the train at 11.30, after stopping by the local Tesco for snacks, and emerged at London Blackfriars Station at around 1 am. I could see The Queue the moment I emerged from the station, creeping along the South Bank, and turned right to follow it about a mile or so to the end, where I joined it just before London Bridge.

I hopped in behind a middle-aged couple, and not long behind me were two men who didn’t show much interest in chatting, so I directed my attention to the pair in front. In front of them was another couple, much younger, and the five of us spent a few minutes doing introductions. When you know you’re going to be standing with someone for a lot of hours, you might as well get to know them, so we did. The couple in front had come up from somewhere on the Dorset coast, the younger couple from somewhere in the midlands. We chatted for pretty much the entire night, and I didn’t realise until afterwards that we never exchanged names. Conversation, naturally, got to why we’d all come, and the stories were all very similar. Respect for the Queen, and a way to say thank you for a life of extraordinary service. And, like me, a desire to simply be a part of it in some small way.

When we got around to logistics, it became clear that the couple in front of me hadn’t really done their research at all. They’d booked a hotel room, checked in and slept for a couple of hours, then left their bags and come to join The Queue. They were hoping to get back in time to sleep and enjoy breakfast at the hotel before checking out. Secretly I thought that was a rather ambitious and probably impossible plan, but I kept that to myself for now.

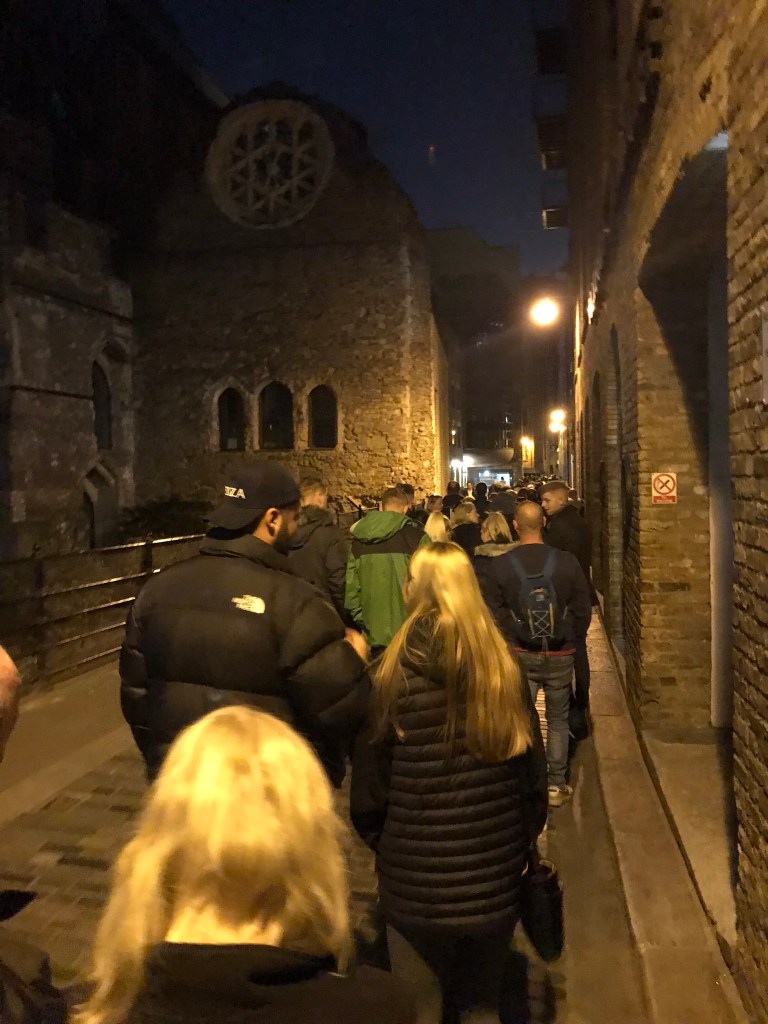

The Queue moved at a steady pace. Only very rarely did it stop altogether, which meant you might be able to lean on the wall or sit on a bench, but it was only ever a few moments, and then we were on the move again. The night was quiet, a cool breeze and the lapping of the Thames were all there was to accompany the gentle hum and chatter that rumbled up and down The Queue as we strode past the Clink Prison Museum, Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre and the Oxo Tower, following our progress on map apps and checking the live tracker every so often to see if it was getting longer or shorter.

It was a dark night – the moon was up, but its light was greatly weakened by competition from the streetlights, bridges and illuminated shopfronts that lined the river. Here and there, buildings remained open after hours for people to use the bathrooms, and we popped in and out with complete faith that we’d be able to get back into the line again. Indeed, when I emerged from the Tate Modern at about 3am the section of queue in front of me was unrecognizable – I had to walk ahead a long way before I saw my new friends looking back and waving to catch my attention. There were no challengers – by that time, each participant knew their neighbours and there was an unspoken agreement that toileting was allowed and anyone who had to duck out should be allowed to duck back in. This was long before the much-touted wristband system was initiated, which turned out to be entirely unnecessary because The Queue was reliably self-regulating in that regard. One or two unrecognizable faces did try to surreptitiously squeeze their way in, but were unceremoniously squeezed back out by people who were justifiably protective of their positions.

As we progressed along the South Bank several of us noticed with despair that many of the usual food carts and vans were closed, and the one or two cafes that were open had off-puttingly long queues. Fortunately I was prepared, and made sure to keep nibbling away at my snacks. Quorn eggs, mini cheddars and a ham and cheese sandwich kept me going, but when I did spot a drinks van open I took the opportunity to grab a hot drink for myself and my new friend, the lady in front of me. Before I got there, she came running to catch up with me, to say she didn’t want one after all, as neither of them had brought their wallets. Thinking this was utter madness (who goes to stand in a queue in London at 1am without a wallet, or any means of acquiring provisions?) I got her a cup of tea anyway, because she was looking distinctly wobbly by that time. As we sipped our tea, I felt a bit of life coming back into my legs and was pleased to see a bit of colour returning to her face. They really haven’t thought this through, I thought, not for the first or last time that night. Both were wearing jackets, but no other warm layers, and she was only wearing ¾ length leggings and trainers. I, on the other hand, was wearing my warm, waterproof boots, thermal leggings and jeans, my thermal top, a jumper and a jacket, and as the night wore on over the early hours, when metabolism slows and body temperature drops, I added a scarf, beanie and an extra jumper. By about 4am my stroll had become more of a waddle, but at least I was just about warm enough. I had a very small bottle of whisky (one of those sample size ones) and whenever I felt my energy levels droop significantly I took a small sip, and that perked me up enough to keep going.

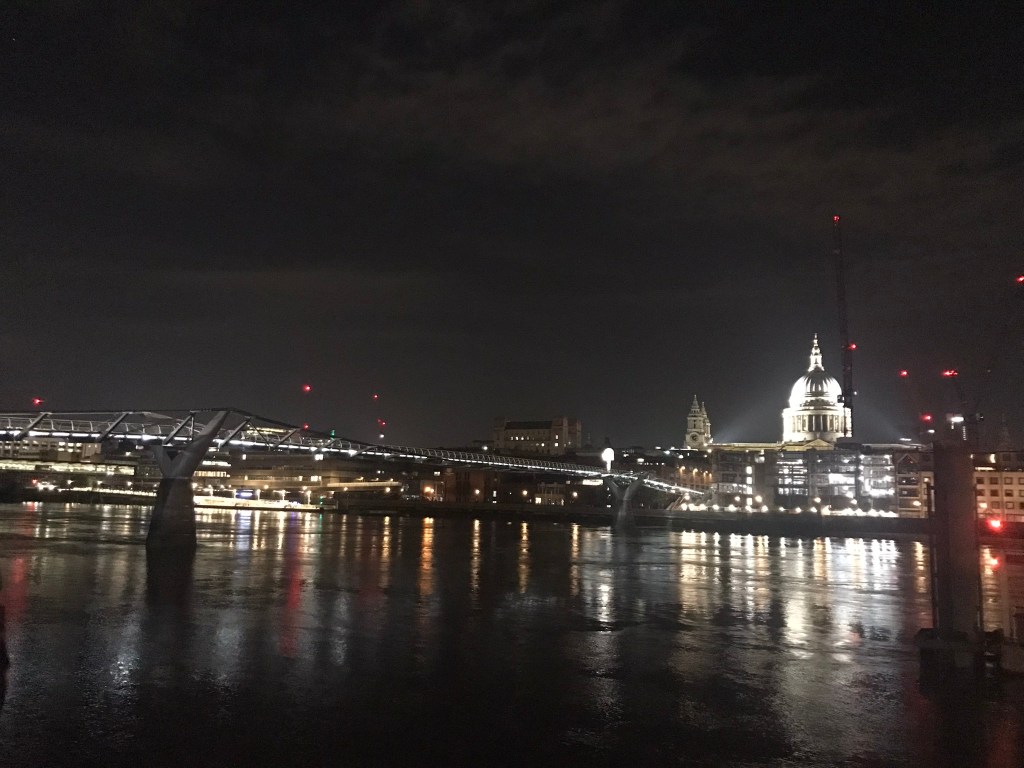

We moved through the night. Across the river, the reflections of St Paul’s Cathedral, the City of London School, Cleopatra’s Needle and other lights of London shimmied and danced in the black vastness of the river that was rippling slightly in the gentle but steady breeze. The moon moved across the sky, and still we trudged on. Conversation never flagged, but was never very intense either. We talked about the weather, how lucky we were that it wasn’t raining (did someone have some brownie points in Heaven, we wondered?) how organised the whole thing was, how the time seemed to be passing surprisingly quickly, who had a story about the royal family, what we all planned for the next day, what the last week had been like. Superficial, maybe, but sustaining, and pleasant, and all underlaid with a sense of shared purpose. Who in their right mind would stand outside in the dark and cold all night for a brief moment in front of a coffin? We would, of course, and in that moment it didn’t matter that the rest of the world thought we were mad.

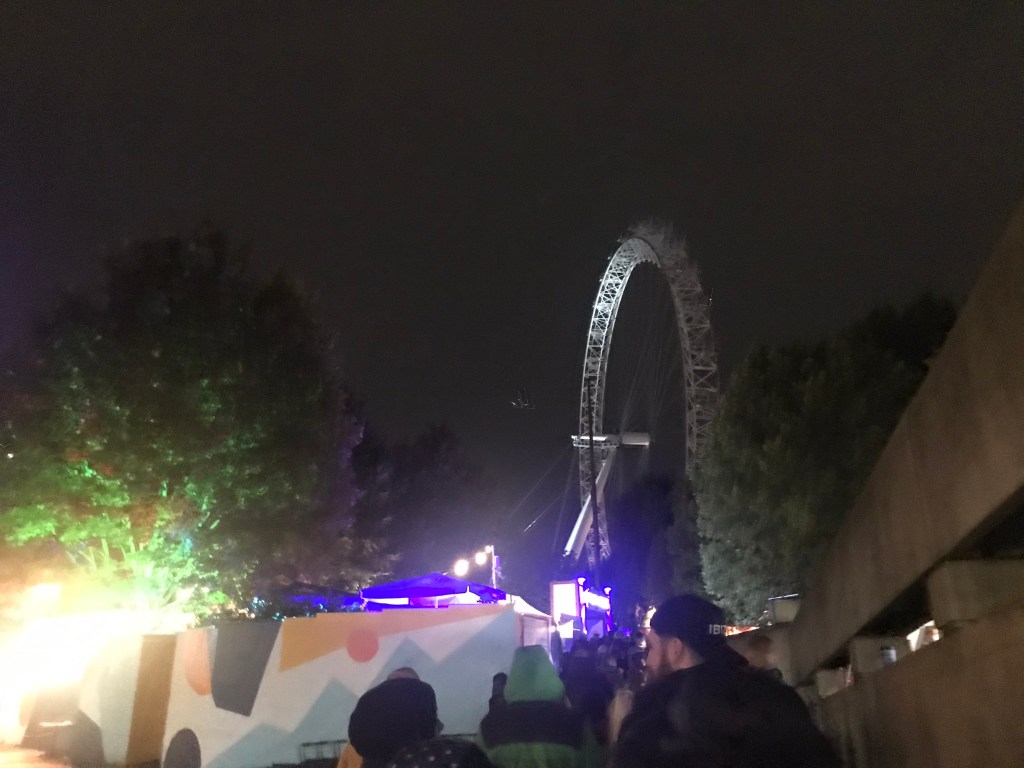

After a few hours, when we were veering to the left to divert round the Eye, we heard a sound, oh so familiar to the night shift workers, the bakers and other early risers – the cry of a bird signalling that dawn was not far away. Soon after that we became aware of an almost imperceptible lightening of the sky to the east, downriver towards the docks, and as we turned left away from the river and were directed behind the Sea Life Museum onto Belvedere Road there was a faint tinge of grey, reassuring us that the dark, deep night was almost over.

It was about at this point that we reached another milestone – we were finally issued with our official wristbands. By now they had become largely redundant as we all knew where our spot was, but it felt nice to log it as a sort of checkpoint. We were on the way, and soon we would be there.

We re-joined the river shortly after that, turning left at Westminster Bridge to walk along the riverbank again. Here we found ourselves passing the National Covid Memorial Wall, which I had not seen before – a collage of a thousand and more messages, images, faces and flowers. It lent a strange sort of perspective to our own pilgrimage, looking at all these lives that had been cut so tragically short.

Things started slowing down a bit at this point, and I could see that my companions were beginning to feel the strain. They hadn’t had anything to eat all night (they refused all my offers to share my snacks), and the woman, in particular, was getting very prickly and went from complaining that they weren’t going to have time for their nap before breakfast, to worrying whether they would even be back for check-out time at all. Meanwhile, the sun rose over a subdued Westminster Palace, its flag flying disconsolately at half-mast and a few solitary boats chugging by without much enthusiasm. It was a dreary morning – dry but overcast and entirely colourless, reflecting the sombre mood of the thousands of souls trudging in unison along the banks of the equally grey surface of the river.

Across Lambeth Bridge we marched, and after convincing my friend in front (a few times) that she could do it and wouldn’t it be a shame to give up at this point, we reached the final test – the Great Snake of Victoria Tower Gardens. This was by far the toughest part of The Queue. We were tired – physically and mentally, by the long, cold march through the night. The sun was now fully up, the sky, in its great, grey shroud, was uninspiring and the sense of adventure, inspired by journeying through the dark into unknown and unprecedented circumstance, had long since worn off. The end was so close, within sight, but we moved towards it so very, very slowly. The snake zigged and zagged, back and forth, forth and back endlessly through the park. We could feel our feet moving, yet the palace seemed to come no closer and the Buxton Memorial Fountain, which marked our entry to the park, seemed to shrink no further away.

The only redeeming feature of this part of The Queue, apart from the indecently cheerful volunteers handing out sweets and snacks on the turns, was the fact that its natural geography brought us right alongside our fellow queuers, not just the ones immediately before and after that we’d spent the night chatting with. Now we had compatriots also on our left and right, recognisable at each turn and along each straight to the next one. We pumped each other up, we cheered each other on. Signs of delirium began to show, mainly in the form of too-much-information style reports on the state of the portaloos, or cackles of excitement as an enthusiastic punter made it around another bend. My friend in front became very grumbly, and made frequents comments about giving up, but all around were shouts of encouragement, of ‘don’t give up now’, and ‘come on, we’re nearly there’, not just in our row but all the way up and down the park.

At last, at about half past eight, when the statue, finally, was discernibly distant, the walls of the palace appeared in front of us and we were directed towards the security screening. I took my last swig of whisky and threw the tiny bottle in the bin along with the rest of my rubbish. I had read up on the rules and knew that I was allowed only one bag, with one zip opening, no liquids of any kind and nothing that might be considered a weapon – it was tighter than airport screening. The couple in front of me, who had nothing but their phones, had obviously taken the advice of ‘don’t bring anything’ a little too literally – meanwhile the younger woman in front of them was having a very loud grumble about her £80 lip gloss being confiscated. My initial thought on this was why on earth would you pay £80 for a lip gloss, but I didn’t ponder it for very long because at this point we were ushered into Westminster Palace’s entrance area, still outside, where the atmosphere had taken on a different feel. There was anticipation now, almost nervousness. A hush had fallen over The Queuers, and each was filled with their own thoughts. This was it, the moment we’d been standing in the dark for nearly eight hours for. What would it be like? What should I do, when my turn comes and I’m standing in front of the coffin?

Then The Queue moved, I turned and found myself standing at the top of a flight of stairs and looking down onto one of the most peculiar and amazing sights I have ever seen. Four lines of people were making their way slowly down to the bottom of the stairs, where they forked to flow around either side of the central dais (called a catafalque, but don’t worry, I won’t test you on that). It was slow and procession like, as if we’d all been told to walk as if we were proceeding down a wedding aisle. In the centre, below where I was standing but raised high above the stream of mourners, was a coffin draped in the coat of arms of the United Kingdom, gold lions blazing against their scarlet background. On top of that was an enormous wreath of flowers and at either end, in all their magnificence, were the crown jewels: the orb, the sceptre and the St Edwards Crown. I’d seen them before, in the Tower of London, but only now, when they were free of their glass confines could I appreciate how superbly crafted and spectacular they were. Was it the morning light, slanting in through the great stained windows, that made them sparkle as brightly as summer sunlight on rippling water? Or was it the moisture in my eyes, that came unbidden as I looked over this scene, the culmination of my long wait through the night?As I made my way down the steps, taking in as much as I could, from the sparkling jewels to the household guards – standing motionless but alert at every corner of the dais, and at strategic points around the hall – to the calm and silence that had descended on the crowd after the noise and bustle outside. So chatty we had been through the night – team mates, almost, bolstering each other’s spirits and relishing the sense of anticipation and occasion. Now we were individuals, each with our own thoughts, contemplations on our role in all this ceremony, and private reflections on the person we were all there to pay tribute to.

My own feelings, at this point, were a furious muddle of anticipation, excitement, nerves (what if the live camera zooms in on me? I must not cry on television!!), indecision as I considered what I would do or say when I finally found myself in front of the coffin, and awe at the sheer spectacle of the Hall. My emotional state, intensified by exhaustion, sleep deprivation and having spent the previous eight hours in a heightened sense of anticipation, was only barely under control. Most people were stopping when they reached the front – some just walked past, but most paused to bow, curtsy, or say a few silent words of thanks. The rules, which I had so thoroughly examined before I left, stated that we were not allowed to stop – but most people paused only for a moment before moving on, and the security team clearly did not have the heart to discourage this. I saw men, women and children, and many cultures and religions represented. It was a marvellous thing to be a part of.

When I finally did step forward and turn to face the coffin, I felt all my emotions come unbidden to the top. As I looked up at the emblazoned images on the flag and the glistening crown, I felt time stop, and the rest of the room fade away, as though it had gone fuzzy at the edges (or it could have been the moisture in my eyes again). The moment felt stretched, though I’m sure it was mere seconds. After all that time wondering what I would do, suddenly it was obvious – I bobbed a tiny curtsey, whispered ‘Thank you, ma’am’, and moved on, sniffing furiously and attempting to stay composed, at least until I was out of the building.

I emerged into bright sunshine, the grey pallor of the day having transformed into glorious blue. I looked around – others were emerging, like me, wiping their eyes and taking deep, heaving breaths. We were emotionally wrung out, exhausted and overwhelmed, but also satisfied. I found my Queue companions, bid them farewell, and stepped out onto the streets of London, anonymous once more. I was tired, yes, but at that moment my overwhelming feeling was one of satisfaction, gratification, and of a mission accomplished. I had done my part, and I could go home, back to the relative obscurity of my village, knowing I had now, at least, done something.

I finished the morning by walking back down Whitehall, across Horse Guards and to Green Park (collecting a very large coffee on the way), where I strolled among the flowers and cards that were being collected there, many of which featured Paddington Bear (I heard later that the stuffed toys were being donated to children’s hospitals). I read several of the messages, and the overwhelming sentiment was one of thanks. Schools, businesses, hospitals, clinics, religious groups, individuals and families and various international communities all expressed their gratitude alongside their condolences. I placed my own, and a few others that had been entrusted to me for the same purpose, and made my way home, sharing a conspiratorial nod with a few people who, like me, were still wearing their wristbands.

Was it tiring? Yes. Emotional? Yes. A lot of effort for a few moments to shed a tear for a woman I never met? Yes. I won’t deny any of that. But was it worth it? Absolutely. It was a unique, historical moment to be a part of and the feeling of camaraderie, the novelty of taking eight hours to walk two or three miles through the night with people I’ll never see again, and the overwhelming spectacle of the jewel-bedecked coffin on its catafalque, is a memory I will always cherish, and, now that I’ve written it down, I’ll be able to remember and share. Some of you will think I’m mad, and some may disapprove altogether, but I for one, will always be glad that I went to London, one last time, to see The Queen.

You left me with tears in my eyes.

A beautiful reflection

LikeLike

Thanks! Hope you had a tissue handy 🙂

LikeLike

Nah, I just sniffed…

LikeLike

Wonderful !

LikeLike